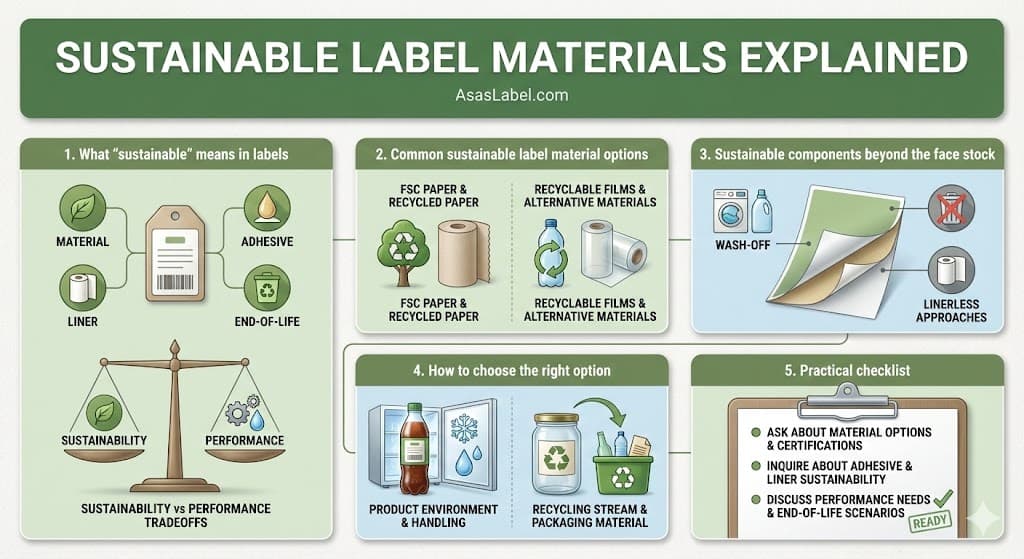

The transition toward eco friendly labels requires looking beyond surface-level aesthetics. A truly sustainable label accounts for the entire lifecycle of the packaging. It encompasses sourcing, production, application, and final disposal. Brands often focus solely on the face stock, yet the environmental impact is a cumulative result of multiple components.

Professional packaging strategies now demand a holistic view of the label composite. This "label sandwich" consists of the face material, the adhesive, and the release liner. Neglecting one layer can render the entire sustainable effort void. For instance, a recyclable paper label with a non-soluble adhesive can contaminate plastic recycling streams.

Understanding the nuances of sustainable label materials drives better decision-making. It moves procurement away from greenwashing and toward quantifiable ecological benefits. This guide dissects the technical and material considerations necessary for implementing effective sustainable labelling strategies.

Sustainability in the context of labeling is a multifaceted compliance challenge. It is not merely about choosing a brown, textured paper that looks natural. It involves rigorous assessment of how that material behaves when it enters the waste stream. The goal is to minimize the environmental footprint without compromising the integrity of the product.

A primary objective is checking if the label supports the circular economy. This means the label should either degenerate harmlessly or facilitate the recycling of the primary packaging. If the label hinders the recovery of the container, it fails the sustainability test regardless of its raw material origin.

Supply chain transparency is also a critical factor. Sourcing materials from responsibly managed forests or using verified post-consumer waste (PCW) ensures that the inputs are as ethical as the outputs. This creates a chain of custody that withstands scrutiny from regulators and eco-conscious consumers.

The face stock is the visible layer that carries the brand design and information. In sustainable packaging labels, this layer often gets the most attention. Options range from papers derived from agricultural waste to bio-based films. However, the face stock acts only as the carrier.

Beneath the face lies the adhesive layer. This chemical component determines whether the label stays put during use and how it behaves during disposal. An eco-friendly adhesive must align with the disposal method of the container. Mismatched adhesives can clog recycling machinery or degrade the quality of recycled resins.

The release liner serves as the delivery system for the label. It is discarded immediately after application, representing a significant volume of industrial waste. Sustainable approaches must address the end-of-life for this silicone-coated by-product. Ignoring the liner ignores nearly fifty percent of the material volume involved in the process.

End-of-life scenarios dictate the material choice. If a package is compostable, every layer of the label must be certified compostable. If the package is destined for the recycling bin, the label must separate easily or be compatible with the recycling process of the main container material.

Sustainable materials often face scrutiny regarding their durability and application performance. A common misconception is that eco-friendly options are inherently fragile or prone to failure. While some early biodegradable materials had limitations, modern engineering has closed the gap significantly.

Trade-offs do exist and must be managed dynamically. For example, high percentage PCW paper may have shorter fiber lengths. This can sometimes affect the tensile strength during high-speed machine application. Converters and brands must adjust tension settings to accommodate these physical properties.

Aesthetics also play a role in this balance. Recycled materials frequently exhibit specks, variations in brightness, or texture differences. While some brands embrace this as a visual cue of sustainability, others view it as a deviation from brand guidelines. Acceptance of these variances is effectively a performance metric in sustainable design.

Resistance to environmental factors is the final hurdle. A compostable label meant to break down in soil must still survive the humidity of a refrigerator or the friction of shipping. Balancing the rate of degradation with the necessary shelf life is the key engineering challenge for compostable labels.

The market for sustainable stock has expanded rapidly. Brands now have access to a diverse portfolio of materials that cater to specific environmental goals. These materials generally fall into categories of recycled content, renewable sources, or recycling-enabling technologies.

Choosing the right category depends on the packaging substrate. The golden rule is to match materials to facilitate monomaterial recycling. Placing a paper label on a paper box is straightforward. Placing a paper label on a plastic bottle requires more technical consideration regarding the recycling separation process.

FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certification remains the gold standard for wood-based label materials. It verifies that the virgin pulp used in the paper comes from responsibly managed forests. This certification ensures biodiversity protection and fair labor practices in the supply chain.

Recycled paper stocks take sustainability a step further by reducing the demand for virgin timber. These papers are categorized by their percentage of Post-Consumer Waste (PCW). A 100% PCW paper is the most ecologically sound option as it closes the loop on paper waste completely.

The manufacturing of recycled paper generally requires less energy and water compared to virgin paper processing. However, the de-inking process can leave residual chemicals. For food, pharmaceutical, or beverage applications, brands must ensure the recycled stock meets safety migration limits and provides an adequate barrier.

Textured and natural-look papers are popular in the luxury and organic sectors. These often utilize waste from other industries, such as cotton rags, grape waste, or barley residue. These "alternative fiber" papers offer a unique tactile experience while reducing reliance on tree pulp.

Plastic labels are not inherently the enemy of sustainability. In fact, for plastic packaging, a matching plastic label is often the best choice for recyclability. Polypropylene (PP) and Polyethylene (PE) films are standard choices. Using a PP label on a PP container creates a mono-material package that can be recycled without separation.

Recycled content films are gaining traction. These films incorporate Percentage Post-Consumer Recycled (PCR) resin. Utilizing PCR reduces the reliance on fossil fuel extraction for virgin plastic production. Availability of high-quality PCR resin is improving, allowing for clearer and stronger film options.

Bio-based films offer a departure from petrochemical sources. These plastics are derived from renewable resources like corn, sugarcane, or wood cellulose. While they reduce carbon footprints during production, their disposal requires careful attention. Not all bio-based plastics are biodegradable; some are chemically identical to standard plastics and should be recycled.

Compostable films, such as PLA (Polylactic Acid) or cellulose based cellophane, are designed for specific end-of-life streams. These materials degrade under industrial composting conditions. They are ideal for brands using compostable packaging vessels, ensuring the entire unit can be processed together without contamination.

Focusing exclusively on the face material is a common amateur error in sustainable packaging design. The chemical and structural components that support the face stock carry significant environmental weight. The adhesive and the liner are invisible to the consumer but visible to the recycling facility.

The interaction between the label and the recycling bath is critical. Efficiency in material recovery facilities (MRFs) depends on predictable behaviors of these components. If an adhesive gums up the shredder or the liner cannot be recycled, the sustainability claim of the product is compromised.

Standard permanent adhesives can be disastrous for PET recycling. When plastic bottles are recycled, they are shredded and washed in a caustic bath. Standard adhesives often hold the label specifically to the PET flake. This contaminates the recycled rPET, causing discoloration and degradation of physical properties.

Wash-off adhesives are chemically engineered to solve this problem. In the caustic bath, the adhesive deactivates. This allows the label (usually a lighter material like PP) to float while the heavier PET flakes sink. This clean separation ensures high-quality rPET yields.

Bio-based adhesives are another avenue of innovation. These formulations use renewable materials rather than petroleum-derived polymers. They are typically paired with compostable labels to ensure that the adhesive does not introduce toxicity into the compost soil during degradation.

Low-residue adhesives are crucial for reusable packaging models. As more brands explore refillable containers, the ability to remove a label cleanly without leaving sticky residue is vital. This extends the lifespan of the primary container, reducing the need for manufacturing new glass or plastic vessels.

The release liner is traditionally a single-use waste product. Glassine paper coated with silicone is difficult to recycle because the silicone disrupts fiber bonding in paper mills. Consequently, tons of liner waste end up in landfills or incinerators annually.

PET liners are an alternative that offers recyclability. Unlike silicone-coated paper, PET liners can be collected and recycled into new polyester products. They are also thinner and stronger, allowing for more labels per roll. This reduces shipping weight and changeover frequency on the application line.

Liner recycling programs are becoming essential for large-scale label users. Suppliers collect the spent liner waste and route it to specialized facilities that can separate the silicone from the substrate. This requires logistical commitment but drastically reduces the industrial waste footprint of the labeling process.

Linerless labels represent the ultimate reduction strategy. These labels are wound like tape, with a release coating on the face of the label beneath. By eliminating the liner entirely, waste is reduced by huge margins. Linerless technology requires specific applicators but offers the highest material efficiency.

Navigating the sea of sustainable options requires a strategic approach. There is no universal "best" material. The correct choice is a variable dependent on the product's lifecycle, the packaging substrate, and the regional recycling infrastructure.

Brands must clarify their sustainability goals. Is the priority to reduce carbon footprint? Is it to eliminate plastic? Is it to facilitate circularity? The answers to these questions will narrow down the material selection significantly and prevent incompatible pairings.

The physical environment the product inhabits dictates the material limits. A paper label, however sustainable, is a poor choice for a shampoo bottle kept in a shower. The water exposure will degrade the fibers, causing the label to retain moisture, mold, or peel off.

Chilled and frozen supply chains present specific challenges. Adhesives must remain tacky at low temperatures, and face stocks must resist condensation. Choosing a material that fails in the supply chain leads to product waste, which is the antithesis of sustainability. Performance must be validated under real-world conditions.

Squeezable containers require flexible films. A rigid bio-based material might crack when the consumer squeezes the bottle, leading to a poor user experience. Polyethylene (PE) films, often available with recycled content, offer the necessary conformability for semi-rigid packaging.

Direct thermal and thermal transfer needs also influence choice. If the label requires variable data printing (like shipping labels or food dates), the material must have a heat-sensitive coating or be compatible with ribbons. Eco-friendly, bisphenol-free (BPA-free) thermal papers are available to ensure chemical safety alongside material sustainability.

The compatibility principle is paramount in sustainable packaging labels. The label material should mimic the container material whenever possible. This is particularly true for plastics. A polyethylene (PE) label on a polyethylene tube enables the entire unit to be recycled as a single stream.

Glass containers offer more flexibility but require specific adhesive considerations. Paper labels are generally accepted on glass as they burn off during the glass remelting process. However, for glass bottles meant to be washed and refilled, a wash-off adhesive with a film label is preferable.

Cardboard and paperboard packaging should ideally be paired with paper-based labels. Introducing a large plastic film label to a cardboard box can interfere with the paper pulping process. The plastic film becomes a contaminant that must be screened out, reducing the efficiency of paper recycling.

Compostable packaging is an all-or-nothing game. If a brand uses a compostable pouch, utilizing a standard plastic label renders the compostability claim invalid. The label, adhesive, and ink must all be certified biodegradable to ensure the package does not introduce microplastics into the soil.

Moving from theory to procurement requires a structured validation process. Suppliers often use vague terminology like "green" or "earth-friendly." Buyers must cut through the marketing language to verify the technical specifications of the materials.

A rigorous checklist ensures that the investment in sustainable labeling yields genuine environmental returns. It protects the brand from reputational risk and ensures compliance with evolving packaging regulations regarding Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).

Start by requesting technical data sheets (TDS) for the face stock and the adhesive. Ask specifically about the percentage of post-consumer waste in the face stock. A vague claim of "recycled content" could mean industrial waste or a very low percentage. Verify that the PCW content is third-party certified.

Inquire about the adhesive's recycling compatibility. Ask if the adhesive is APR (Association of Plastic Recyclers) critical guidance recognized. For glass applications, ask for evidence of wash-off capabilities. If the supplier cannot provide this data, they have not validated the sustainability of their product.

Demand clarity on the liner waste. Ask if the supplier offers a liner take-back program or if the liner contains recycled content. The availability of a recycling outlet for the liner is often the differentiator between a truly circular partner and a standard vendor.

Question the origin of bio-based materials. Ensure that bio-plastics are not competing with food sources. Second-generation feedstocks (agricultural waste) are preferable to first-generation feedstocks (crops grown specifically for plastic). This distinction addresses the ethical implications of land use.

Finally, ask for lifecycle assessment (LCA) data. Reputable suppliers can model the carbon footprint reduction of switching from a standard material to their sustainable alternative. This data is invaluable for internal reporting and external marketing claims.