Packaging engineers and brand managers frequently misinterpret the functional boundaries between recyclable and compostable labeling solutions. This confusion leads to contamination in recycling streams and performance failures in the supply chain.

Selecting the correct eco-label is not merely a marketing decision but a technical necessity dictated by the primary container’s end-of-life cycle. You must match the label attributes to the recovery infrastructure available for the package itself.

Understanding the precise chemical and mechanical differences between these two pathways is critical. A misalignment here does not just negate sustainability efforts; it often renders the entire package waste.

The terms recyclable and compostable utilize fundamentally different recovery mechanisms that are rarely compatible. Industry professionals must move beyond surface-level definitions to understand the material science governing these claims.

The primary error lies in assuming these terms describe the material's origin rather than its disposal destination. A bio-based material is not automatically compostable, and a plastic material is not automatically recyclable in every context.

Recyclability is defined by the capacity of the label to travel through a Material Recovery Facility (MRF) without hindering the recovery of the primary container. It is a rigorous technical standard involving separation efficiency and contamination thresholds.

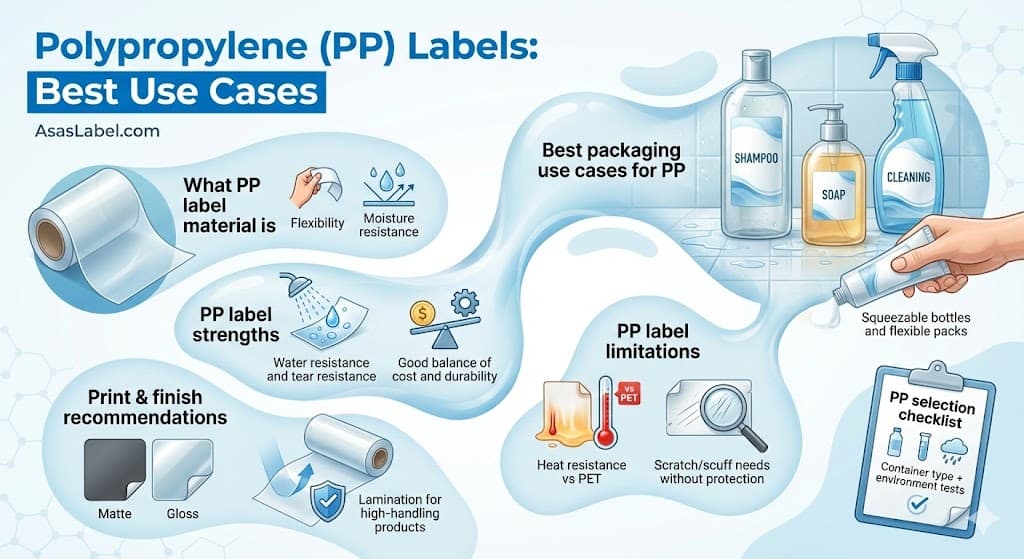

For a label to be genuinely recyclable, the facestock must generally match the polymer of the container. For example, a polypropylene (PP) label on a PP bottle allows the entire unit to be reground and melted into pellets without separation.

Alternatively, the label must utilize specific adhesive technologies designed to detach cleanly during the wash process. In PET recycling streams, the label must float while the PET flakes sink, necessitating a precise specific gravity differential.

Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) guidelines dictate that the ink, adhesive, and coating must not discolor or chemically degrade the resulting recycled resin. If the label bleeds ink into the wash water, it compromises the value of the entire batch.

Therefore, "recyclable" signifies compatibility with the aggressive mechanical and chemical environment of industrial recycling lines. It is about recovering high-quality raw material for a second life.

Compostable labels are engineered to break down biologically into carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic compounds within a specific timeframe. This process relies on microbial activity rather than mechanical processing.

Certification is non-negotiable here. A label is only compostable if it meets standards like ASTM D6400 or EN 13432. These standards verify that the material disintegrates completely and leaves no toxic residue or heavy metals in the resulting humus.

Brands must distinguish between industrial composting and home composting. Industrial facilities reach high temperatures (up to 60°C) that accelerate degradation, allowing for breakdown of tougher biopolymers.

Home compostable materials must break down at much lower ambient temperatures. Using an industrially compostable label on a package destined for a backyard bin will result in a label that remains intact for years, effectively acting as litter.

Crucially, compostability includes every layer of the label construction. The adhesive, the face material, and the topcoat varnish must all pass toxicity and biodegradability testing to carry the claim validly.

The decision matrix for selecting label stock relies entirely on the primary package substrate. Attempting to mix recycling and composting streams creates logical failures that confuse consumers and degrade waste systems.

A "sustainable" label on the wrong package increases the environmental burden. The goal is a unified package structure where the label and container share a single end-of-life destination.

Rigid plastic containers used for beverages, detergents, and personal care products almost exclusively require recyclable label solutions. The infrastructure for PET and HDPE recovery is widespread and economically viable.

When labeling PET bottles, the industry standard is a polypropylene roll-fed label or a pressure-sensitive label with wash-off adhesive. This ensures the valuable PET yields remain pure for conversion into rPET.

Glass jars also fall into the recycling-first category. While glass is melted at high temperatures, organic matter burns off, but label residues can cause aesthetic defects. Wash-off adhesives are standard protocol here to ensure clean cullet.

Aluminum cans present a unique challenge. While direct print is common, brands using shrink sleeves or pressure-sensitive labels must ensure these materials burn off completely without affecting the aluminum smelt quality.

Standard polyethylene (PE) flexible films should be paired with PE labels. This creates a mono-material structure that can ostensibly be recycled where store drop-off streams for flexible plastics exist.

Compostable labels excel in food service environments where the packaging is likely to be contaminated with organic residue. Biodegradable containers that cannot be rinsed effectively are the ideal hosts.

Molded fiber bowls, bagasse clamshells, and PLA bioplastic cups are designed for industrial composting. Applying a standard vinyl or BOPP label to these containers ruins their compostability, forcing the sorter to landfill the entire item.

Fresh produce labeling is another critical sector. Fruit stickers (PLU labels) are infamous contaminants in home and industrial compost piles. Switching to certified home compostable PLU sticker materials solves a major contamination headache for organic waste processors.

Brands selling zero-waste solid toiletries, such as shampoo bars wrapped in paper, should utilize compostable paper labels with bio-based adhesives. This aligns with the consumer's expectation of a plastic-free disposal limit.

Any packaging explicitly composed of starch blends, cellulose, or PHA aimed at the organics bin requires a label that degrades at the same rate as the vessel. Mismatched degradation rates can lead to localized soil toxicity.

Transitioning to specific eco-labels introduces technical limitations. Sustainable materials rarely offer the identical performance characteristics of traditional fossil-fuel incumbents without engineering adjustments.

Procurement teams must evaluate these limitations against product lifecycle requirements. Ignoring physical constraints leads to label flagging, fading, or total adhesion failure before the product reaches the consumer.

Recycling-friendly labels, particularly those made from standard PP or PE, offer excellent durability. They resist moisture, oils, and friction, making them suitable for shower environments or outdoor exposure.

However, wash-off adhesives used in recycling applications can be sensitive to high humidity. If the bond is designed to break in water, extreme ambient humidity or cooler condensation must be tested to prevent premature release.

Compostable labels endure significantly tighter performance constraints. Because they are designed to degrade in the presence of moisture and microbes, they are inherently less stable in wet environments.

Cellulose-based clear films or sugarcane papers are highly hygroscopic. They absorb water, which can cause wrinkling, bubbling, or peeling if the product is stored in an ice bucket or high-humidity refrigerator.

Shelf life is a concern for compostable materials. The adhesives often have a shorter expiration timeline (often 6 to 12 months) before they begin to crystallize or lose tack, unlike standard acrylics that last years.

Brands utilizing compostable labels on frozen goods must verify the adhesive's service temperature range. Many bio-based adhesives become brittle and fail at sub-zero temperatures.

Recyclable materials benefit from massive economies of scale. High-volume production of BOPP and PE facestocks keeps costs comparable to traditional non-sustainable options.

The premium for recycling-friendly labels usually lies in the specialized wash-off adhesive technology rather than the films themselves. However, as these become industry standards, the price gap is narrowing.

Compostable raw materials face distinct supply chain volatility. The market for PLA films, wood pulp based papers, and proprietary bio-polymers is smaller, resulting in higher Minimum Order Quantities (MOQs).

Cost per unit for compostable labels is consistently higher—often 30% to 50% more than standard counterparts. This is driven by the cost of certifying bodies, lower extrusion volumes, and expensive feedstock.

Lead times for compostable stocks are frequently longer. Converters may not keep master rolls of specific compostable structures in inventory, necessitating custom orders that slow down speed-to-market.

Brands must also budget for rigorous testing. Validating a new compostable structure on a high-speed application line ensures the material doesn't tear, which incurs upfront engineering costs.

A label is a composite laminate, not a single material. Sustainability claims are frequently invalidated because one layer of the "sandwich" does not meet the necessary criteria.

Packaging engineers must dissect the label into its three primary constituents: the face material, the adhesive, and the release liner. Neglecting any one of these leads to non-compliance.

Adhesives are the most complex variable in sustainable labeling. A compostable paper face paired with a standard acrylic adhesive renders the label non-compostable because the acrylic introduces persistent microplastics into the soil.

Certified compostable adhesives are formulated from renewable content or specific synthetic polymers that mineralize completely. These formulations are sensitive and require precise handling during the converting process.

For recyclable claims, the adhesive chemistry dictates the "washability." Hot melts and aggressive rubber-based adhesives often lock the label to the container, preventing separation in the float/sink tank.

Inks and protective varnishes also play a role. UV-cured inks are generally technically durable but can inhibit composting speed by sealing the cellulose fibers from microbial attack.

Heavy metal content in inks is strictly regulated under standards like EN 13432. Brands must ensure their converters use compliant ink sets that do not exceed toxicity thresholds for soil amendments.

The release liner is the largest waste stream generated during the labeling process. While it does not end up on the package, its disposal impacts the brand's total environmental footprint.

Standard glassine liners are silicone-coated paper. While technically recyclable, the silicone coating contaminates paper streams, meaning they are frequently landfilled or incinerated.

PET liners are gaining traction for recyclable supply chains. If the brand already uses PET recycling streams, some regions allow for the collection and recycling of PET liners, creating a circular loop.

For compostable labels, the liner is problematic. There are very few certified compostable release liners on the market. Most brands using compostable labels still generate landfill waste via the liner.

Printing technologies limit material choices. Direct thermal printing on compostable materials requires phenol-free chemistry to remain non-toxic. This limits the availability of variable data options for things like shipping labels.

Digital printing offering shorter runs is viable for both streams, but the primer and toner compatibility with composting standards must be verified certificate by certificate.

Navigating the legal and ethical landscape of sustainability claims requires a systematic approach. Greenwashing accusations arise when brands oversimplify complex disposal processes.

Regulatory bodies like the FTC (in the US) and the CMA (in the UK) are cracking down on vague environmental terminology. Precision is your best defense against litigation and consumer backlash.

Never use the term "biodegradable" on consumer-facing packaging. It is broad, scientifically vague, and legally risky. Always specify "Compostable" and qualify it with "Industrial" or "Home" based on your certification.

Verify that your claim covers the entire finished package. If you put a compostable label on a non-compostable bottle, you cannot market the package as compostable. You must explicitly state "Compostable Label" to avoid deceiving the buyer.

Utilize standardized icons like the How2Recycle label. These systems force you to conduct a technical review of your packaging inputs (container + cap + label) to determine the accurate disposal instruction.

Check for regional availability. Marking a package as "Recyclable" implies that 60% of households have access to facilities that accept it. If you use a niche recyclable material, you may need "Check Locally" qualifers.

Obtain physical certificates from your suppliers. A datasheet claiming "compost compliant" is insufficient. Demand the TUV Austria, BPI, or equivalent certificate number for the specific face-adhesive combination you are purchasing.

Conduct real-world degradation testing. If pursuing industrial composting, send samples to a local facility to verify they actually process your specific packaging format, regardless of theoretical lab results.

Avoid mixing messages. Do not design a label that looks like brown craft paper to imply "natural" if the material is actually standard plastic. Visual cues create consumer expectations regarding disposal that must aid, not hinder, the sorting process.

Ultimately, the choice between recyclable and compostable labels is not about which sounds greener. It is about aligning with the existing infrastructure to ensure the material stays in the economy or returns safely to the earth.