Procurement professionals understand that the final unit price of a label is rarely arbitrary. It represents a strict summation of raw material availability, machine time, and the inevitable rigidities of manufacturing physics. Understanding these inputs allows for better negotiation and more accurate forecasting.

Price fluctuations often stem from commodity shifts in pulp and petrochemical markets. However, the conversion process itself holds the most leverage for optimization. Analyzing the cost structure reveals where efficiency is lost and where value is engineered.

The goal is not simply finding the cheapest converter. The goal is identifying the most efficient manufacturing pathway for a specific SKU profile. We will dissect the cost centers that define your pricing matrix.

Volume remains the primary dictator of label pricing logic. The fundamental tension exists between fixed setup costs and variable running rates. Short runs suffer from the disproportionate weight of make-ready time compared to actual printing time.

As quantity increases, the amortized cost of setup dilutes significantly. This creates a steep price curve that eventually flattens. Identifying the exact break-even point between different printing technologies is crucial for cost control.

Print technology selection drives the base cost structure. Digital press rates operate somewhat linearly compared to analog methods. There is minimal setup, but the unit cost generally remains static regardless of volume due to click charges and ink costs.

Flexographic printing offers an inverse economic model. The setup is expensive and labor-intensive, creating a high barrier to entry for low volumes. However, as the press speeds increase and runtime lengthens, the per-unit cost drops aggressively.

SKU proliferation fragments total volume, often increasing costs even if the aggregate quantity remains high. Ten orders of 5,000 labels cost significantly more than one order of 50,000 labels due to the necessity of halting production for plate changes and color matching.

Lead time requirements also influence pricing variance. Rush orders disrupt scheduling efficiency, forcing converters to break long runs or incur overtime labor. Standardized lead times allow for optimized gang-run scheduling, which reduces waste and passes savings back to the buyer.

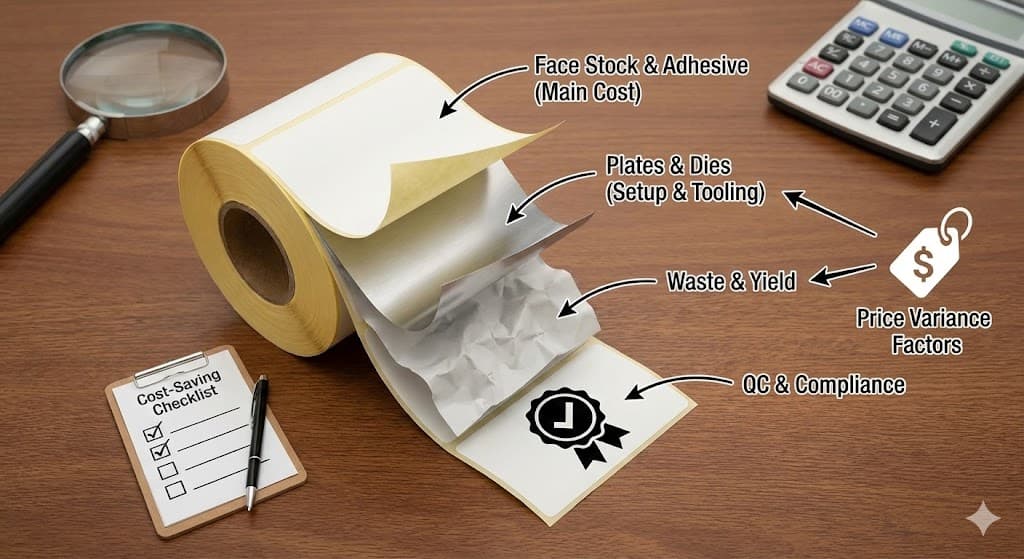

The physical composition of the label accounts for a massive percentage of the total spend. This includes the face sheet, the liner, and the chemistry holding them together. Unlike fixed tooling costs, material costs scale linearly with volume.

Material selection must balance performance with economics. Over-engineering a specification for a short-lifecycle product bleeds margin. Conversely, under-specifying a material leads to application failure, which incurs replacement costs far exceeding the initial savings.

Paper substrates generally offer the most economical entry point. However, direct thermal or thermal transfer coatings add cost layers. The source of the pulp and the complexity of the coating process dictate the fluctuating base price of these commodities.

Synthetic films like Polypropylene (PP) and Polyethylene (PE) command higher prices due to their durability and petrochemical origins. The production process for films is energy-intensive, and pricing tracks closely with oil market indices.

Specialty face stocks, such as metallic foils or textured wines stocks, introduce premium pricing. These materials often have higher minimum order quantities (MOQs) from the raw material supplier, forcing the converter to carry inventory or charge for full master rolls.

Adhesive chemistry is the invisible cost driver. Standard permanent acrylics are the baseline. Modifications for high-tack applications, freezer grade requirements, or removability require specialized formulations that increase the raw material cost per square inch.

Release liner selection is often overlooked but impacts the bottom line. Glassine liners are standard for automatic application speeds. PET liners allow for faster dispensing and reduce web breaks, potentially saving money on the application line despite a higher upfront material cost.

Ink coverage affects pricing, particularly in digital printing where cost is calculated by click charges or ink volume. Heavy coverage or total flood coats consume more consumables, directly impacting the quote. Flexo ink is generally cheaper but still accumulates cost on long runs.

Specialty inks add significant expense. Metallic, fluorescent, or color-shifting inks require more expensive pigments. Adding a tactile varnish or a spot UV coating requires an additional print station, increasing both material use and machine complexity.

Non-recurring engineering (NRE) costs and per-run setup charges are distinct fiscal elements. Tooling represents physical assets that must be manufactured, stored, and maintained. Setup represents the time and labor required to configure the press.

Amortization strategies differ by supplier. Some converters absorb tooling costs into the unit price to lower the barrier to entry. Others line-item these expenses to keep the unit price transparent and scalable. Understanding this allocation is vital for long-term contract comparison.

The complexity of the label design dictates the tooling requirement. Irregular shapes, intricate pervious cuts, or multi-layer constructions require precision-engineered tools. These are capital expenditures that must be accounted for in the initial onboarding.

Flexographic printing requires a physical photopolymer plate for every color station. A four-color process job requires four plates. A job with two additional spot colors requires six plates. The cost multiplies with design complexity.

Plate technology has evolved, with HD flexo plates offering higher resolution but demanding more expensive processing equipment. The lifespan of a plate is finite. High-abrasion inks or millions of impressions will eventually degrade the image, necessitating replacement costs.

Mounting tapes and cylinders are part of the hidden setup structure. Plates must be mounted on cylinders using specific density tapes to control dot gain. This manual labor is a billable pre-press activity that occurs before the press even starts.

Digital printing eliminates the plate cost entirely. The trade-off is the higher variable running cost. For SKUs that change artwork frequently, the savings on plate manufacturing often justify the higher unit price of digital production.

The die distinguishes the label shape from the waste matrix. Flexible dies are thin sheets of magnetic steel that wrap around a magnetic cylinder. They are cost-effective and standard for most pressure-sensitive label runs.

Solid rotary dies are machined from a single steel cylinder. These are significantly more expensive but necessary for long-run durability or cutting through difficult thick substrates. The investment in a solid die makes sense only for high-volume, repeat production.

Standard shapes usually incur no tooling charges because converters maintain a library of common sizes. Custom shapes require custom tooling. Creating a new die involves CNC machining and hardening, a cost passed directly to the buyer.

Die maintenance is an ongoing consideration. Dies dull over time, especially when cutting abrasive thermal coatings or paper dust. The cost of re-sharpening or replacing dies is typically factored into the manufacturing overhead or charged when print quality degrades.

Material yield is the ratio of sellable labels to total raw material consumed. No printing process is 100% efficient. The difference between the purchased roll length and the shipped label count is waste, and intrinsic to the cost model.

Setup waste is unavoidable. In flexography, operators must run material through the press to register colors and set pressure settings. Depending on the press complexity, this can consume hundreds of feet of stock before a single sellable label is produced.

Web path waste refers to the material required to thread the machine from unwind to rewind. Larger presses with more print stations have longer web paths. This creates a fixed waste amount every time a roll is changed or a job is set up.

Running waste occurs during production. Press stops, speed changes, or splice detections can cause registration generated errors. Converters factor a specific scrap percentage into their pricing to cover these inevitable production anomalies.

The matrix is the ladder of waste material left after the labels are die-cut. If the gap between labels is excessive, you are paying for material that ends up in the landfill. Minimizing the matrix gap improves material utilization.

Edge trim is required to ensure clean rolls. Master rolls are often slightly wider than the final print width to allow for web wandering. This slit waste ensures the final rolls have perfect edges but contributes to the total material usage variance.

Disposal costs are rising. Converters must pay to dispose of matrix waste, which often contains mixed materials (silicone liner, adhesive, face stock) that are difficult to recycle. These environmental compliance costs are embedded in the overhead rates.

Quality control is a labor and technology cost center. Ensuring that labels meet strict brand standards and regulatory requirements requires investment in verification systems. This is not optional for regulated industries like pharmaceuticals or food.

Automated vision systems are installed on modern presses to detect defects in real-time. These systems compare every printed label against a digital master file. The capital cost of this equipment is amortized into the hourly press rate.

Color management requires spectrophotometers and standardized lighting environments to measure Delta E values. Maintaining consistent brand colors across different production runs involves ink formulation labor and precise documentation.

Post-print inspection involves slitter-rewinders where operators or cameras check for missing labels, splices, or poor die cuts. This secondary step adds a labor component to the manufacturing workflow but ensures 100% accurate roll counts.

Regulatory compliance demands documentation. For medical or UL-certified labels, the converter must maintain traceability records for raw materials and inks. The administrative burden of maintaining these certifications is reflected in the supplier's operational costs.

Sample retention and archival processes utilize storage and administrative resources. Keeping retain samples for a specified period protects both the buyer and supplier in case of disputes, but it adds to the facility's overhead.

Reducing label spend requires a collaborative approach with manufacturing partners. Small adjustments in specifications can yield significant improved production efficiency. The focus should be on eliminating waste and maximizing machine throughput.

Analyze the total cost of ownership rather than just the label unit price. A cheaper label that causes application line failures or brand inconsistencies costs more in the long run. Strategic procurement focuses on value engineering.

Consolidating sizes allows for the use of common dies. If five products utilize the same dimension, setup times drop, and tooling costs vanish. Standardization enables the combination of multiple SKUs into single production runs.

Review material specifications across the entire product portfolio. Reducing the number of unique face stocks or adhesives allows the converter to buy raw materials in larger bulk volumes, securing price breaks that can be shared.

Consult with the converter during the design phase. Slight modifications to artwork can reduce the number of color stations required. Replacing a spot color with a CMYK build reduces plate costs and setup time.

Optimize the label shape for the web. Irregular shapes that do not nest well create excessive matrix waste. Designing shapes that allow for tighter imposition on the web maximizes material yield and lowers the cost per thousand.

Evaluate tolerance requirements. Demanding tighter registration or die-cut tolerances than necessary slows down press speeds and increases waste rates. accurate, functional tolerances ensure quality without imposing artificial production constraints.